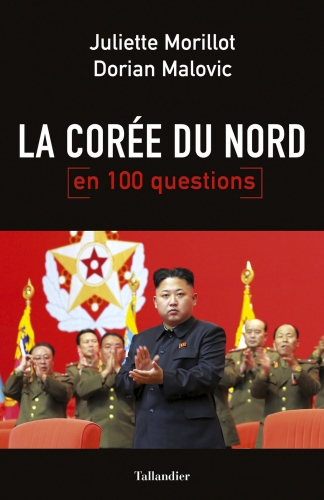

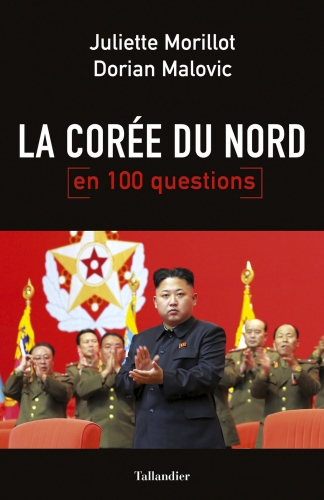

Le voyage d’Alain Soral en juillet 2017 en Corée du Nord (officiellement appelée République démocratique populaire de Corée ou RPDC) a électrisé les réseaux sociaux et suscité les nombreux commentaires de la « Dissidence ». Certains se félicitaient de ce séjour tandis que d’autres s’élevaient contre une nouvelle apologie du national-bolchevisme. Si Alain Soral pense y voir un modèle national et socialiste, on peut se demander s’il n’aurait pas pris connaissance auparavant de La Corée du Nord en 100 questions de Juliette Morillot et Dorian Malovic.

Composé de cent réponses regroupées en sept parties (« Histoire », « Politique », « Géopolitique », « Réalités », « Économie », « Société et culture » et « Propagandes »), cet ouvrage est probablement le meilleur disponible sur le sujet en langue française. Il se complète parfaitement avec le remarquable essai du correspondant du Monde au Japon, Philippe Pons, Corée du Nord. Un État-guérilla en mutation (1). Parfois sollicitée par les médiats dominants, Juliette Morillot présente l’avantage déterminant de lire, de parler et de comprendre le coréen.

Quelques vérités dérangeantes

À l’heure où l’entité yankee d’un Donald Trump aux abois et quasiment soumis à certaines coteries bellicistes de l’« État profond » US menace l’intégrité territoriale d’un État en légitime défense, La Corée du Nord en 100 questions apporte un éclairage lucide et objectif sur cet État supposé voyou. « Pays mystérieux pour les Occidentaux, la Corée du Nord est davantage une énigme que la caricature à laquelle les médias étrangers la réduisent depuis des années. De l’ignorance naissent les fantasmes (pp. 15 – 16). » Abomination pour les uns, « nouvelle Sparte » si possible nationale-bolchevique pour les autres, la RPDC sert de prétexte pour toutes les fantasmagories possibles et imaginables, peut-être parce que le coréen serait l’une des langues les plus difficiles au monde (avec le français…). Instructif et plaisant, l’ouvrage de Morillot et Malovic présente le grand mérite de lever des équivoques.

Les auteurs remarquent que « la République populaire de Corée est sans doute l’un des rares pays pour lesquels faire fi de toute déontologie, affabuler ou ne pas vérifier ses sources est couramment accepté, même dans les grands titres de presse. C’est aussi l’un des rares pays au monde où l’on ressuscite régulièrement (pp. 343 – 344) ». Des victimes purgées supposées éliminées réapparaissent en public quelques temps plus tard… Ils abordent des sujets dérangeants peu connus en Occident qui, triturés dans un certain sens, relèvent de la désinformation. Par exemple, « comment les réfugiés nord-coréens sont-ils manipulés ? (p. 347) » Ils expliquent « qu’un véritable commerce lucratif du témoignage a vu le jour en Corée du Sud : depuis quelques années, les témoignages auprès des journalistes ou des chercheurs sont rétribués (ce qui n’était pas le cas encore au début des années 2000). Selon un principe : plus les témoignages sont terrifiants, plus ils sont chers. Ce commerce du poids de l’horreur est entretenu à la fois par les journalistes avides de spectaculaire et par des organisations humanitaires, souvent chrétiennes, voulant financer des opérations de “ sauvetage ”. En outre, le ministère sud-coréen de l’Unification a institutionnalisé le procédé. Fin 2015, une heure d’entretien coûtait entre 60 et 600 dollars (pp. 352 – 353) ». Il faut par conséquent plus que jamais se méfier d’une littérature misérabiliste soi-disant rédigée par des réfugiés qui submerge l’Europe. Les auteurs qualifient ces productions d’« indigestes (p. 219) », truffés « d’incohérences (p. 219) ». Un certain Bandi y fait un réquisitoire virulent contre la RPDC, « à ceci près que le livre ne tient pas la route pour qui lit le coréen (p. 219) ».

Ignorant les us et coutumes du confucianisme, les Occidentaux excellent en outre dans les interprétations erronées ou fallacieuses. « Au palais-mémorial de Kumsusan à Pyongyang, où se trouvent les dépouilles de Kim Il Sung et de Kim Jong Il, s’incliner n’est pas une marque d’allégeance mais simplement de politesse et de respect, pour les défunts tout autant que pour le pays hôte (p. 358). » En visite officielle à Paris, l’invité de la République française ne s’incline-t-il pas devant la tombe du Soldat inconnu ? Et s’il se rend en Israël, ne rallume-t-il pas la flamme à Yad Vashem ?

Les Occidentaux s’indignent de l’absence de liberté d’expression en Corée du Nord qui se montre sourcilleuse sur ce point. C’est compréhensible. « Bien sûr, n’est pas le bienvenu un visiteur s’adressant à un passant ou à une serveuse de restaurant pour critiquer le régime ou pour poser de but en blanc, au nom de la liberté de parole, des questions jugées personnelles (p. 357). » Est-ce si différent en Allemagne, dans l’Hexagone ou aux États-Unis où des nationalistes blancs présents à Charlottesville en août 2017 ont perdu leur emploi ? Essayez donc dans un restaurant parisien branché de critiquer Macron, d’approuver Dieudonné ou, pis, d’évoquer certains thèmes interdits de l’histoire contemporaine. « Aux yeux du régime, il n’y a pas de “ prisonniers politiques ” (p. 208) » comme dans l’Hexagone républicain. Si la justice hexagonale ne condamne pas aux camps de travail, elle peut prononcer des stages de citoyenneté qui sont une forme douce (et insidieuse) de rééducation mentale. La mort sociale rôde sous Marianne, mais plus silencieusement (et avec l’hypocrisie des droits de l’homme, de la femme, de l’humain et du trans…).

Tradition et patriotisme

Les Coréens du Nord assimilent dans un syncrétisme propre à leur esprit bouddhisme, confucianisme et même chamanisme bien qu’officiellement interdit. Ils en ont gardé une vraie curiosité pour certaines pratiques. La grave crise des années 1990 l’a même relancé au sein des familles et en particulier auprès des femmes. Bien qu’ouverte aux vents de l’ultra-modernité, la Corée du Sud fortement christianisée a elle aussi recours à de tels actes animistes comme en témoigne l’entourage de la présidente destituée Park Geun-hye. Toutefois, depuis 1945, les deux Corées divergent de plus en plus et rendent toute réunification effective impossible. Ce constat se vérifie par la langue. Aujourd’hui tant dans le vocabulaire que par la grammaire, le coréen du sud correspond moins au coréen du nord même si les locuteurs se comprennent toujours. La différence d’ordre anthropologique concerne le triomphe au Sud de l’individualisme. Les auteurs soulignent en revanche la primauté du cadre holiste sur le désir individualiste. « Le “ nous ” (uri) et l’intérêt de la collectivité (famille, clan, société) priment l’individu, le “ je ” (na) (p. 319). » Le contraste sociologique, voire anthropologique, entre les deux Corées est si saisissant que de nombreux exilés nord-coréens préfèrent finalement quitter leur nouveau foyer hyper-sophistiquée et ses reproches malveillants envers leurs habitudes estimées trop « ringardes ».

Ce qui irrite l’Occident dégénéré à l’heure des sociétés ouvertes est le caractère clos de la partie septentrionale de la nation coréenne. « L’homogénéité du peuple coréen a toujours été considérée comme une qualité intrinsèque, intimement liée à l’histoire de la péninsule (p. 299). » Ce vigoureux sentiment national repose sur une histoire tragique. « Au cours des âges, une bonne demi-douzaine de troupes étrangères piétinèrent les terres coréennes : khitan, liao, jurchet, mongoles, japonaises, mandchoues et même françaises en 1866, lors d’une malheureuse expédition militaire conduite par l’amiral Roze en représailles du martyre de missionnaires français, qui se termina par la débâcle des soldats de Napoléon III (p. 29). » Se succèdent ensuite les Chinois, les Russes, les Japonais, les Soviétiques et les Étatsuniens. L’acquisition d’armes nucléaires grâce à la collaboration fructueuse des ingénieurs pakistanais résulte de ces tourments tragiques. Pyongyang se souvient toujours qu’en 1951 et en 1953, le général MacArthur proposa des frappes nucléaires préventives. « Le chantage que la Corée du Nord exerce, loin d’être le fruit de dirigeants paranoïaques, est au contraire le résultat d’une réflexion construite pour servir des objectifs stratégiques clairs. Se voiler la face en qualifiant les leaders nord-coréens de “ fous ” est une illusion aux allures de stratégie d’évitement… (p. 153). »

Conseillés par le général Étienne Copel, les auteurs qui n’évoquent pas le programme spatial de la Corée du Nord, préviennent que « les armes nord-coréennes ne sont pas offensives mais dissuasives avant tout, elles ont pour but d’éviter toute intervention (américaine surtout) sur le territoire national. Il s’agit de la doctrine classique de dissuasion nucléaire, défendue par les grandes puissances elles-mêmes (p. 158) ». Pyongyang applique la dissuasion nucléaire théorisée par les généraux français des années 1960. Ils insistent encore que « dans le storytelling occidental, on oublie de rappeler que le programme nucléaire vise également à légitimer le régime et son leader aux yeux du peuple nord-coréen à qui il est demandé de grands sacrifices en échange (p. 158) ». Le nationalisme atomique coréen du Nord se doute que « personne […] ne serait assez fou pour affecter son arsenal nucléaire à la protection d’un pays tiers, écrit le romancier “ à clef ? ” Slobodan Despot. C’était, dans son implacable logique, une épée qu’on ne tirait du fourreau que pour se protéger soi-même, en dernier recours. Tout autre utilisation vous exposerait au risque d’un contre-feu apocalyptique. Les nations non atomiques ne pouvaient donc que compter sur elles-mêmes et se plier au chantage des puissants (2) » Par conséquent, face aux sanctions imposées par une pseudo-« Communauté internationale », véritable mafia d’authentiques États voyous, « la résilience de la Corée du Nord vient d’une réalité simple : elle a si peu qu’elle n’a rien à perdre et elle s’est adaptée pour supporter les privations au point que le régime exploite ces votes de l’ONU pour cimenter le peuple contre les “ agresseurs extérieurs ”. Au fond, les sanctions sont inefficaces car personne ne souhaite vraiment qu’elles le soient (p. 193) ». La Corée du Nord n’entend pas obtempérer aux injonctions de la grotesque CPI (Cour pénal international) et suit le précédent édifiant des États-Unis d’Amérique.

La force nucléaire nord-coréenne dorénavant constitutionnalisée est clairement un moyen de pression pour que Washington négocie avec Pyongyang dont les « exigences » ne sont pas insurmontables : reconnaissance par Washington de la RPDC, établissement d’une ambassade US, signature d’un pacte de non-agression avec les États-Unis, levée de toutes les sanctions de l’ONU, signature d’un traité de paix avec Séoul et « assurance de pouvoir poursuivre librement son programme nucléaire civil (p. 148) ». Les États-Unis craignent de tels pourparlers d’autant que compétents, polyglottes et cultivés, les diplomates nord-coréens suscitent l’effroi de leurs homologues yankees plus habitués à éructer des ordres qu’à discuter sereinement…

Pourquoi cette haine envers un peuple qui n’occupe aucun autre État de la planète et qui n’a aucune responsabilité dans les « camions fous » à Nice, Berlin et Londres ? « Avant d’être dirigée par un régime autoritaire, la Corée du Nord est une nation peuplée d’êtres humains avec une sensibilité, une culture et une inébranlable fierté d’appartenir à un pays, qu’envers et contre toute logique ils aiment profondément (p. 17). » L’individualiste égoïste et exhibitionniste numérique occidental a oublié que l’homo hierarchicus naguère étudié par Louis Dumont (3) persiste en Corée du Nord. Le holisme organise la société en « 25 niveaux de songbun […] et 55 niveaux de kaechung […] eux-mêmes regroupés en trois sous-catégories (p. 293) ». À cette stratification complexe s’intègrent les inminban (groupes du peuple), c’est-à-dire des associations de quartier d’une trentaine de foyers supervisées par des femmes qui assurent la surveillance de proximité. Faut-il pour autant parler d’un « régime d’extrême droite » comme l’affirme Brian Reynolds Myers (4) ? Certes, « les mariages avec des étrangers sont interdits (p. 299) ». En 2006, l’organe officiel du Parti des travailleurs de Corée (PTC), le Rodong Shinmun, titrait : « Une société multinationale et multiraciale est une menace pour la nation ». Or cette sortie très politiquement incorrecte n’a jamais été reprise. Juliette Morillot et Dorian Malovic soulignent plutôt que la RPDC a toujours soutenu Nelson Mandela et le combat de l’ANC contre l’apartheid en Afrique du Sud. Membre du Mouvement des non-alignés, la Corée du Nord défend la cause palestinienne, récuse le mondialisme du FMI et de la Banque mondiale et apporte un soutien moral à la République arabe syrienne du président Bachar al-Assad. Toutefois, le Premier ministre nord-coréen fut invité à une séance du Forum de Davos avant que l’invitation soit décommandée au lendemain du cinquième essai nucléaire.

Une économie balbutiante

« Contrairement à tout ce qui peut s’écrire sur ce pays supposé socialiste et collectiviste, l’économie nord-coréenne vit depuis une dizaine d’années une véritable métamorphose (p. 269). » Désormais, « l’économie d’État ne peut plus garantir du travail pour tous et les exclus du système socialiste sont à disposition pour le secteur privé (p. 270) ». L’« État le plus fermé de la planète » s’ouvre enfin au monde en dépit des sanctions onusiennes qui ne frappent jamais un autre petit État lui aussi détenteur de la bombe atomique, violeur permanent des résolutions du Conseil de sécurité et oppresseur depuis plus de soixante-dix ans d’un autre peuple… Le VIIIe Congrès du PTC en mai 2016 a entériné un plan quinquennal 2016 – 2020, « le premier lancé depuis les années 1980 (p. 265) ». Parallèlement émerge une proto-bourgeoisie, une « classe d’affaires », les donju (ou « maîtres de l’argent », souvent liés à différents cercles du pouvoir.

Ceux-ci s’adaptent au gouvernement de Kim Jung Un (prononcez « Œune ») depuis 2011, un dirigeant dépeint par les médiats occidentaux d’une manière toujours très négative. « De même que pendant des années le monde occidental a entretenu à propos de Kim Jong Il le mythe trompeur d’un pantin excentrique aux confins de la folie, le portrait que dressent les médias de son fils, se limitant à sa coupe de cheveux ou à son embonpoint, est tronqué (p. 106). » Sous sa direction, le PTC a retrouvé son rôle moteur perdue au temps de Kim Jung Il qui s’en méfiait, si bien que la stratocratie portée par le songung redevient une partitocratie que le Parti anime dans le cadre du Front démocratique pour la réunification de la patrie aux côtés du Parti social-démocrate de Corée et du Parti Chondogyo-Chong-u issu d’une révolte populaire, nationaliste, religieuse et xénophobe au XIXe siècle.

C’est un fait patent et assumé : le nationalisme imprègne toute la société coréenne ainsi que toutes les générations. « Le nationalisme atteindra en RPDC un degré inconnu ailleurs dans le monde communiste, explique Philippe Pons. Il trouve son origine dans le patriotisme radical né en réaction à la colonisation japonaise dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle : une revendication identitaire forgée par des historiens coréens qui firent de la nation, pensée en tant qu’ethnie (minjok), le sujet du grand récit national, que le régime reprit à son compte (5). » De ce fort sentiment national découle le fameux concept de juche. Remontant au XIXe siècle, le terme est « employé pour la première fois le 18 mai 1955 par Kim Il Sung, qui, lors d’une réunion de l’une des cellules du Parti des travailleurs, appela à réfléchir sur l’idéologie de façon à réinterpréter de façon créative le marxisme-léninisme en luttant contre le dogmatisme et le formalisme (pp. 74 – 75) ». « D’abord placée sur le même plan que le marxisme-léninisme, poursuit Philippe Pons, la doctrine juche allait supplanter celui-ci en instaurant une “ voie coréenne vers le socialisme ” qui fait de la nation, et non plus du prolétariat, le sujet de l’histoire (6). » Il est dès lors assez comique (et triste) qu’en France, des souverainistes acharnés et des nationalistes-révolutionnaires convaincus, farouchement sociaux et radicaux, maintiennent dans leur tête un autre Mur de Berlin, s’acoquinent avec les va-t-en guerre atlantistes et dénigrent un État lointain qui ne les gêne en rien. La Corée du Nord porte-t-elle une quelconque responsabilité dans l’élection de Macron ou dans la présente déferlante migratoire ?

L’ultime État souverain du monde ?

Conscient de la vulnérabilité de son État, Kim Il Sung a très tôt adopté – et bien avant le Roumain Nicolae Ceausescu – une démarche souverainiste et décisionniste. « Trois concepts, piliers du juche, sont indissociables de la doctrine : tout d’abord, le chaju, l’indépendance politique et diplomatique (égalité totale avec les nations étrangères, respect de l’intégrité territoriale, non-intervention et indépendance nationale). Toutefois, ce chaju ne peut être atteint que si au préalable l’autosuffisance économique (charip) a été réalisée. Vient enfin l’autonomie militaire (chawi), elles-même garante du chaju (p. 75). » En mai 2016, le VIIIe Congrès a réaffirmé « l’indépendance du pays vis-à-vis des grandes puissances (chaju), grâce aux développements de l’économie (charip) et de l’arme nucléaire (chawi) permettant un dialogue d’égal à égal envers les grandes puissances (chaju) (p. 76) » au nom de la nouvelle doctrine du byongjin, la « double poussée » économique et stratégique, qui remplace le songun (« priorité à l’armée »), d’où des changements institutionnels majeurs.

Organe suprême depuis 1999, la Commission de la Défense nationale est remplacée par une Commission des affaires de l’État. Nouvelle instance présidée par Kim Jung Un, par ailleurs président (et non secrétaire général) du PTC, ce nouvel organisme constitutionnel « coiffe l’armée, le Parti et le gouvernement (p. 109) ». Cette modification institutionnelle propre à l’idiosyncrasie politique de la Corée du Nord confirme les analyses de Carl Schmitt dans son État, mouvement, peuple (7) parce que « Armée, Parti, État et peuple sont désormais confondus (p. 90) » (8). En 1982, Alain de Benoist jugeait pour sa part que « c’est à l’Est que se maintiennent avec le plus de force – une force parfois pathologique – des notions positives telles que la conception polémologique de l’existence, le désir de conquête, le sens de l’effort, la discipline, etc. Les sociétés communistes sont à la fois les plus hiératiques et les plus hiérarchiques (du grec hiéros, “ sacré ”) du monde, tandis que les sociétés occidentales réalisent, par le moyen du libéralisme bourgeois et de l’individualisme égalitaire, cela même que voulait Marx – et que le communisme institué s’est avéré incapable de faire passer dans les faits. Formidable exemple d’hétérotélie ! (9)».

Les bruits de bottes yankees s’entendent tout au long de la Zone démilitarisée sur le 38e parallèle le plus surmilitarisé de l’histoire. Washington s’agace d’un État qui ose lui résister, ce qui déplaît aux vils détritus pourris de la colline du Capitole. Suite à une attaque préventive de son fait, Washington pourrait fort bien exiger des autres membres de l’OTAN l’application de l’article 5, ce qui ferait des troupes européennes de la chair à canon appréciable. On ne peut pas renvoyer dos à dos un État assiégé et une superpuissance sur le déclin. La paix en Asie du Nord-Est est menacée par une bande de cow boys trop sûrs d’eux. En cas de conflit, souhaitons seulement qu’un excellent missile nord-coréen coule l’USS Harvey Milk du nom de ce politicard californien qui avait déjà au cours de sa vie l’habitude de recevoir de gros calibres…

Georges Feltin-Tracol

Notes

1 : Philippe Pons, Corée du Nord. Un État-guérilla en mutation, Gallimard, 2016. Pour ce texte, nous appliquons comme cet auteur et à la différence de Juliette Morillot et Dorian Malovic « l’ordre coréen et la transcription du Nord (où nom et prénom s’écrivent avec trois majuscules) (p. 9) ».

2 : Slobodan Despot, Le rayon bleu, Gallimard – NRF, 2017, pp. 67 – 68.

3 : Louis Dumont, Homo hierarchicus. Le Système des castes et ses implications, Gallimard, coll. « Tel », 1979.

4 : Brian Reynolds Myers, La Race des purs. Comment les Nord-Coréens se voient, Éditions Saint-Simon, 2011.

5 : Philippe Pons, « Au pays du nationalisme farouche », dans Le Monde des 10 et 11 septembre 2017.

6 : Idem.

7 : Carl Schmitt, État, mouvement, peuple. L’organisation triadique de l’unité politique (1933), Kimé, 1997.

8 : On retrouve ce triptyque, devenu ici une intéressante quadripartie politique, dans les écrits du penseur nationaliste-révolutionnaire argentin Norberto Ceresole (1943 – 2003), en particulier dans Caudillo, Ejército, Pueblo. La Venezuela del Comandante Chávez (1999), Ediciones Sieghels, 2015, non traduit en français.

9 : Alain de Benoist, Orientations pour des années décisives, Le Labyrinthe, 1982, pp. 69 – 70, souligné par l’auteur.

• Juliette Morillot et Dorian Malovic, La Corée du Nord en 100 questions, coll. « En 100 questions », Tallandier, 2016, 381 p., 15,90 €.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

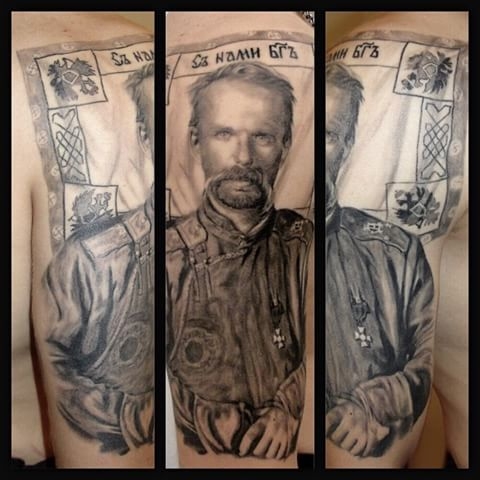

Le baron Ungern-Sternberg a été rendu célèbre par la description qu’en fit Ossendowski dans son fameux « Bêtes, hommes et Dieux », récit de ses voyages à travers la Mongolie. La figure du baron n’est d’ailleurs pas étrangère au succès du livre tant il semble concentrer en sa personne toutes les qualités qui font le charme si mystérieux de l’ouvrage, à commencer par le titre. « Bête, homme et Dieu » : il est tout à la fois. Au demeurant, il plane autour de lui comme un halo de légende qui, comme pour le récit d’Ossendowski, rend difficile de faire la part entre l’histoire et le mythe. Mais, si l’histoire d’Ossendowski, à l’image de celle d’Ungern, est pleine d’épisodes fabuleux très probablement inventés, il faut rappeler qu’elle fut accrédité pour l’essentiel par René Guénon, y compris des éléments parmi les plus merveilleux, lorsqu’il fit paraître, en réponse aux détracteurs d’Ossendowski, Le Roi du Monde, qui replace certains éléments du récit sur un plan initiatique.

Le baron Ungern-Sternberg a été rendu célèbre par la description qu’en fit Ossendowski dans son fameux « Bêtes, hommes et Dieux », récit de ses voyages à travers la Mongolie. La figure du baron n’est d’ailleurs pas étrangère au succès du livre tant il semble concentrer en sa personne toutes les qualités qui font le charme si mystérieux de l’ouvrage, à commencer par le titre. « Bête, homme et Dieu » : il est tout à la fois. Au demeurant, il plane autour de lui comme un halo de légende qui, comme pour le récit d’Ossendowski, rend difficile de faire la part entre l’histoire et le mythe. Mais, si l’histoire d’Ossendowski, à l’image de celle d’Ungern, est pleine d’épisodes fabuleux très probablement inventés, il faut rappeler qu’elle fut accrédité pour l’essentiel par René Guénon, y compris des éléments parmi les plus merveilleux, lorsqu’il fit paraître, en réponse aux détracteurs d’Ossendowski, Le Roi du Monde, qui replace certains éléments du récit sur un plan initiatique.

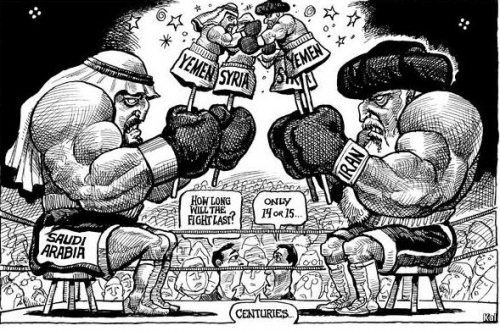

Les auteurs insistent aussi sur les origines du programme nucléaire de dissuasion nationale conçu avec l’aide d’ingénieurs pakistanais. La détention d’un arsenal atomique garantit le maintien de ce régime hybride national-communiste ultra-souverainiste au moment même où Washington revient sur sa parole à propos de l’accord conclu avec la République islamique d’Iran. L’ouvrage fait enfin découvrir au lecteur l’existence de plusieurs territoires coréens.

Les auteurs insistent aussi sur les origines du programme nucléaire de dissuasion nationale conçu avec l’aide d’ingénieurs pakistanais. La détention d’un arsenal atomique garantit le maintien de ce régime hybride national-communiste ultra-souverainiste au moment même où Washington revient sur sa parole à propos de l’accord conclu avec la République islamique d’Iran. L’ouvrage fait enfin découvrir au lecteur l’existence de plusieurs territoires coréens.

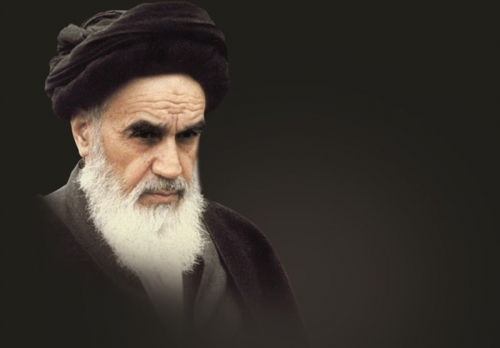

La première partie de l’ouvrage est consacrée à un examen de la pensée de Khomeini avant 1979. Le lecteur y apprendra que dans son ouvrage Le Gouvernement du juriste, paru en 1970, Khomeini prend à contre-pied la tradition religieuse chiite qui se veut historiquement quiétiste et détachée des choses politiques. En théorisant l’institution du velayat-e faqih (traduit par le gouvernement du juriste ou du jurisconsulte), Khomeini entend répondre aux attentes messianiques chiites quant au retour de l’Imam caché (1) et « refonder le rapport des religions à l’autorité politique » (p. 25) en défendant un lien fondamental entre le domaine religieux et le domaine profane. Si ce projet est alors minoritaire au sein des intellectuels chiites, il a des précédents historiques importants : dès le XIIIe siècle, des penseurs ont imaginé une tutelle des mollahs sur la société afin de palier à l’absence de l’imam. Au XVIIe siècle, l’école osuli a créé le titre de marja-e taqlid (la source d’imitation), conçue comme une extension du pouvoir des imams. Le précédent le plus important est probablement celui de la période suivant de près la révolution constitutionnelle de 1905. En 1907, les religieux constitutionnalistes forment en effet un conseil religieux à même de contrôler la validité des lois (p. 28). J. Fabiani estime que Khomeini a synthétisé ces précédents tout en critiquant fermement le processus de sécularisation et de dé-islamisation engagé par le Shah à partir de 1970. Néanmoins, si la révolution fut islamiste, l’aura de Khomeini fut avant tout politique. Ce n’est qu’à partir de 1978, alors en exil à Paris, que Khomeini diffuse des enregistrements de discours mâtinés de références à la martyrologie chiite. Il procède alors à l’islamisation d’un mouvement avant tout social, dirigé contre la monarchie et la sécularisation à marche forcée menée par le Shah depuis la révolution blanche et les réformes de 1963. Le Shah était parvenu à s’aliéner l’intégralité des acteurs sociaux importants, du monde paysan aux grands propriétaires. Descendus dans la rue, ces acteurs participaient à une révolution nationale qui fut pourtant rapidement canalisée grâce à un dénominateur commun : l’islam (pp. 46-47). Le clergé chiite devint, en effet, un relai important de la contestation sûrement parce qu’il s’agissait là d’une institution bien ancrée dans le tissu social et fortement hiérarchisée.

La première partie de l’ouvrage est consacrée à un examen de la pensée de Khomeini avant 1979. Le lecteur y apprendra que dans son ouvrage Le Gouvernement du juriste, paru en 1970, Khomeini prend à contre-pied la tradition religieuse chiite qui se veut historiquement quiétiste et détachée des choses politiques. En théorisant l’institution du velayat-e faqih (traduit par le gouvernement du juriste ou du jurisconsulte), Khomeini entend répondre aux attentes messianiques chiites quant au retour de l’Imam caché (1) et « refonder le rapport des religions à l’autorité politique » (p. 25) en défendant un lien fondamental entre le domaine religieux et le domaine profane. Si ce projet est alors minoritaire au sein des intellectuels chiites, il a des précédents historiques importants : dès le XIIIe siècle, des penseurs ont imaginé une tutelle des mollahs sur la société afin de palier à l’absence de l’imam. Au XVIIe siècle, l’école osuli a créé le titre de marja-e taqlid (la source d’imitation), conçue comme une extension du pouvoir des imams. Le précédent le plus important est probablement celui de la période suivant de près la révolution constitutionnelle de 1905. En 1907, les religieux constitutionnalistes forment en effet un conseil religieux à même de contrôler la validité des lois (p. 28). J. Fabiani estime que Khomeini a synthétisé ces précédents tout en critiquant fermement le processus de sécularisation et de dé-islamisation engagé par le Shah à partir de 1970. Néanmoins, si la révolution fut islamiste, l’aura de Khomeini fut avant tout politique. Ce n’est qu’à partir de 1978, alors en exil à Paris, que Khomeini diffuse des enregistrements de discours mâtinés de références à la martyrologie chiite. Il procède alors à l’islamisation d’un mouvement avant tout social, dirigé contre la monarchie et la sécularisation à marche forcée menée par le Shah depuis la révolution blanche et les réformes de 1963. Le Shah était parvenu à s’aliéner l’intégralité des acteurs sociaux importants, du monde paysan aux grands propriétaires. Descendus dans la rue, ces acteurs participaient à une révolution nationale qui fut pourtant rapidement canalisée grâce à un dénominateur commun : l’islam (pp. 46-47). Le clergé chiite devint, en effet, un relai important de la contestation sûrement parce qu’il s’agissait là d’une institution bien ancrée dans le tissu social et fortement hiérarchisée.

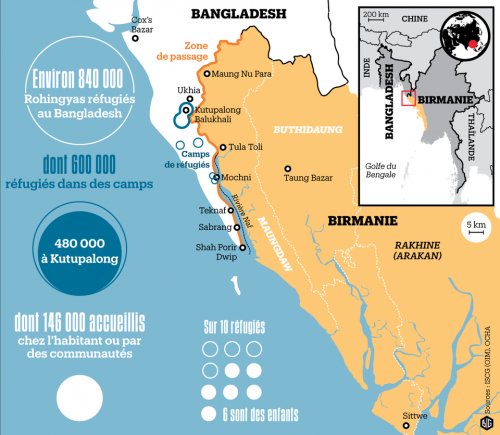

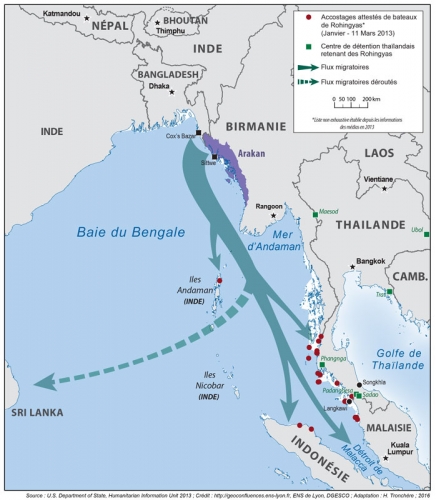

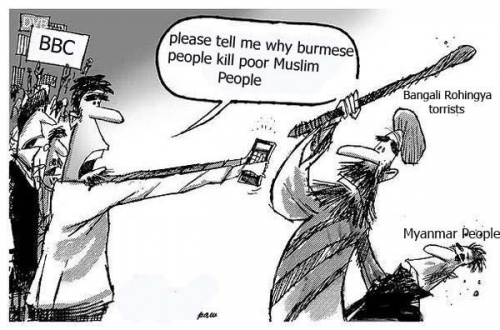

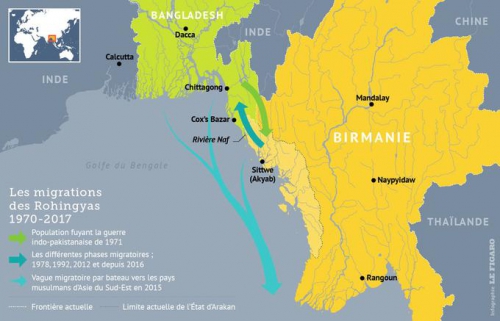

Cet ultimatum, typique du jihad démographique, étant resté sans réponse, les jihadistes bengalis d’Arakan attaquèrent les villages bouddhistes, notamment autour de Maungdaw, avec le lot habituel de pillages, viols, incendies, enlèvements contre rançon, etc.

Cet ultimatum, typique du jihad démographique, étant resté sans réponse, les jihadistes bengalis d’Arakan attaquèrent les villages bouddhistes, notamment autour de Maungdaw, avec le lot habituel de pillages, viols, incendies, enlèvements contre rançon, etc.

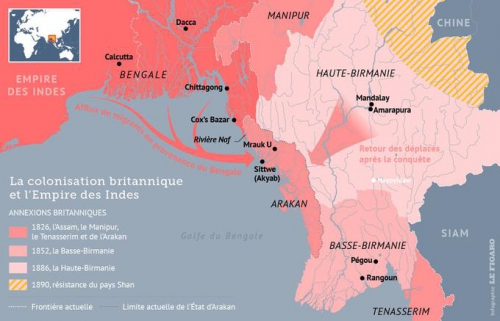

Les Rohingya, descendants lointains de commerçants et de soldats arabes, mongols et turcs, se sont convertis à l'Islam au 15e siècle, alors qu'à l'époque la région était un État vassal du Bengale. Des colonies musulmanes existent en Arakan (Rankine ou Rakhine) depuis la venue des Arabes au 8e siècle. Les descendants directs des colons arabes vivent au centre de l'Arakan près de Mrauk U et de Kyauktaw.

Les Rohingya, descendants lointains de commerçants et de soldats arabes, mongols et turcs, se sont convertis à l'Islam au 15e siècle, alors qu'à l'époque la région était un État vassal du Bengale. Des colonies musulmanes existent en Arakan (Rankine ou Rakhine) depuis la venue des Arabes au 8e siècle. Les descendants directs des colons arabes vivent au centre de l'Arakan près de Mrauk U et de Kyauktaw.